In a new NBER working paper, David G. Blanchflower and Carol Graham analyze several different datasets for the U.S. And provide extensive evidence on the middle age patterns, new evidence of how they differ across the married and unmarried—which is not the case in most other wealthy countries, and review new work on well-being and mortality among the elderly.

The past decade has brought increasing concern, in countries all over the world, of declines in mental health and well-being. Across countries, chronic depression and suicide rates peak in midlife. In the U.S., deaths of despair are most likely to occur in these years, and the patterns are robustly associated with unhappiness and stress. There is also a less-known relationship between well-being and longevity among the elderly, particularly for those over age 70. In this paper, we analyze several different data sets for the U.S. And provide extensive evidence on the middle age patterns, how they differ across the married and unmarried, and review new work on the elderly. The relationship between well-being and aging has a robust association with trends that can ruin lives and shorten life spans. It applies to much of the world’s population and links to behaviors and outcomes that merit the attention of scholars and policymakers alike.

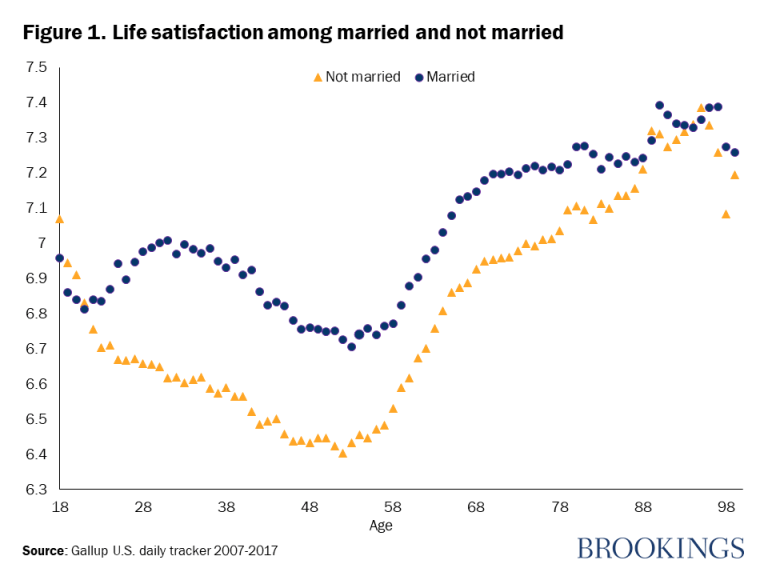

Life satisfaction in the US follows a U-shape during working age, from eighteen through retirement, with a mid-life low in the mid-forties. This is especially clear when controls are included and for those who are unmarried even without controls.

The United States is different, not least as it has higher marriage rates, a lower mean age at first marriage and higher divorce rates than other advanced countries. The young married in the US also experience a decline in wellbeing from around age thirty to midlife but that is preceded by a slight uptick to around age thirty.

Well-being rises for both the married and the unmarried, with and without controls from there to normal retirement age around age 65. Once adjustments are made for differential mortality rates, with those with lower well-being likely to die early, life satisfaction then declines, particularly after age 80, driven especially by widowhood and health shocks.